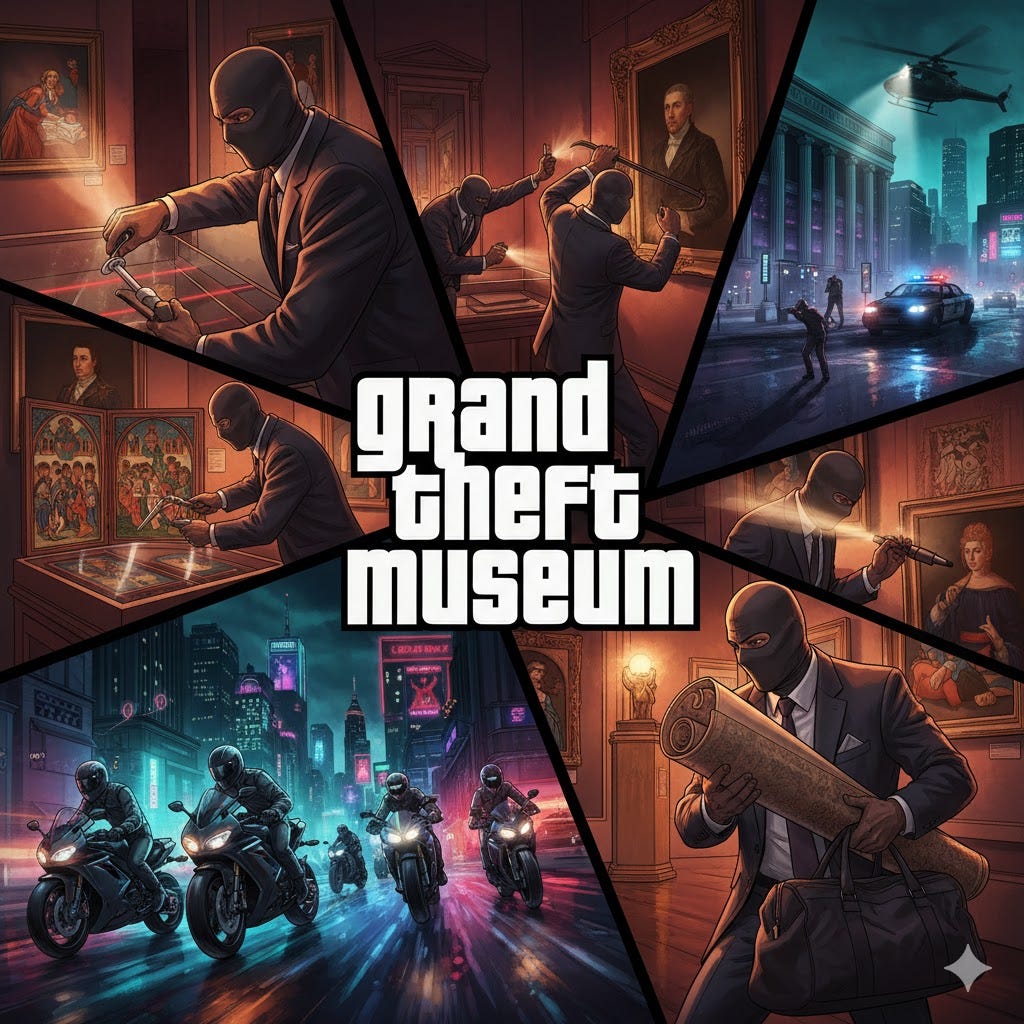

Part 1 - Grand Theft Museum - The Biggest Burglaries in History

Sunday morning, the Louvre lost priceless treasures in seven minutes. This isn't the first time. These are the stories that came before.

This Sunday, 19 October 2025, at half past nine in the morning, a four-person commando gained entry to the Louvre via a cherry picker, cut through the windows of the Galerie d’Apollon with an angle grinder, smashed two high-security display cases and made off with eight imperial jewels in precisely seven minutes.