How Monet's cataracts changed modern art

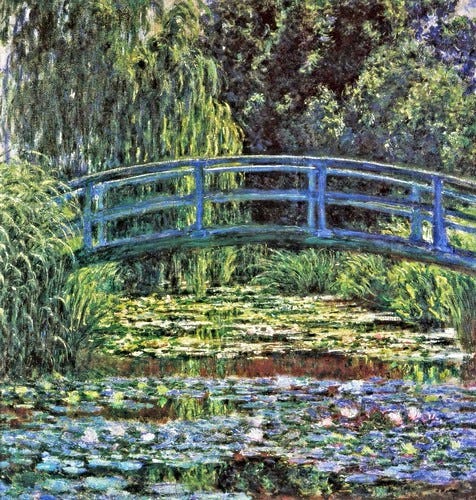

Everyone knows Monet's Japanese bridge at Giverny. But do you know the story behind the 50 paintings he made of it? A story of sight, loss, and how it accidentally changed modern art.

Spring 1883. Through the train window, the meadows of the Seine valley roll past in green bands. Poplars follow one another along the riverbank. Monet watches. He is 42, his greying beard already turning white at the temples.

His suitcases sit at his feet. Inside, a few belongings, tubes of paint, letters from his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel who is finally starting to sell a few canvases.

The train slows as it approaches Vernon. Through the window, Monet glimpses a village clinging to a hillside. Houses with slate roofs, orchards in bloom, a church. Giverny.

The years behind him have been hard. In 1879, his wife Camille died of tuberculosis at 32, in poverty. Since then, Monet has been living with Alice Hoschedé and their eight children. He has two, she has six. Ernest Hoschedé, Alice’s husband, has abandoned his family. Alice chose Monet. Marriage is impossible whilst Ernest lives.

He seeks somewhere stable. Water, light, a garden.

The train stops at Vernon. Monet steps onto the platform.

Three days later, he signs a lease for a pink-walled house in Giverny. A hectare of land, an orchard on a slope. In April 1883, the tribe moves in.

The villagers observe this family’s arrival. An unknown painter, a woman still married elsewhere, eight children. In this conservative rural corner of Normandy, people whisper, refuse to greet them.

Monet doesn’t care.

He transforms the orchard into a chromatic field. Tears out the box hedges, plants thousands of flowers in colour bands. He wants the eye to carry far from his doorstep to the far end of the grounds. A perspective that changes each week.

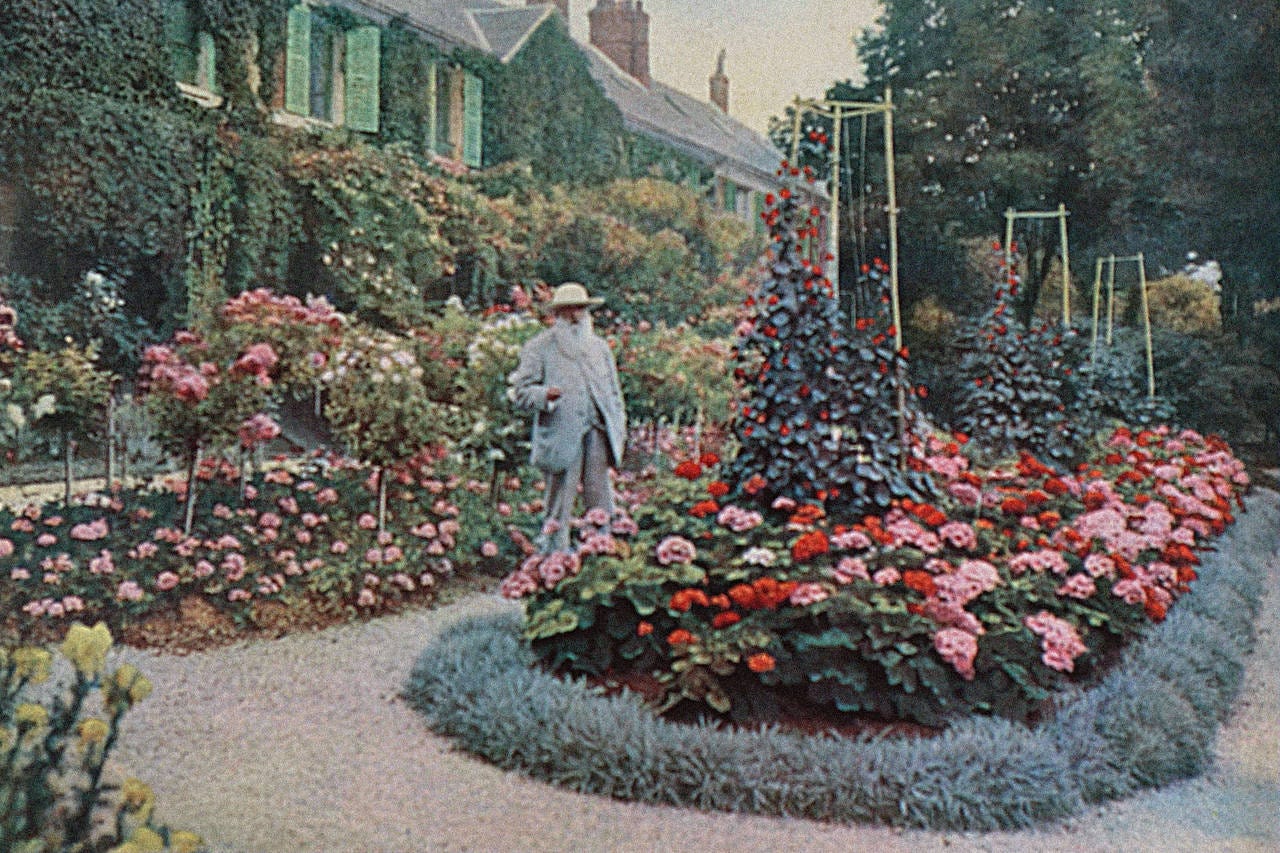

The neighbours nickname him “the painter-gardener”. On his table, the crockery bears Japanese motifs. On the walls, prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige.

In 1891, Ernest Hoschedé dies. The following year, Monet marries Alice.

His paintings sell well in the United States. Money comes in. In November 1890, Monet purchases the house he had been renting. He is a homeowner at 50.

He eyes the land opposite.

The Bridge

On the other side of the railway line lies a marshy field. A branch of the Epte, the Ru, runs through it.

In February 1893, Monet buys the land. He wants to dig a pond, plant water lilies, build a Japanese bridge.

The municipality refuses. The farmers protest. Monet persists. The prefect overrules them.

Late August 1893, workers start digging. Forty metres by fifty. To span the end of the pond, Monet commissions a small wooden bridge. Slightly arched, curved railings. Exactly like those in the Japanese prints.

In Japan, these bridges are painted vermilion red. Monet has his painted green. So it blends into the vegetation.

By autumn 1893, the bridge is complete. Bare, without a trellis. A simple green wooden arch.

Monet plants bamboo, willows, Japanese maples. In 1894, he orders from the botanist Joseph Bory Latour-Marliac hybrid water lilies created through crossbreeding: pink, yellow, purple. The only wild European water lilies are white.

The First Time

One January morning in 1895, Monet sets up his easel facing the pond.

He paints the bridge for the first time.

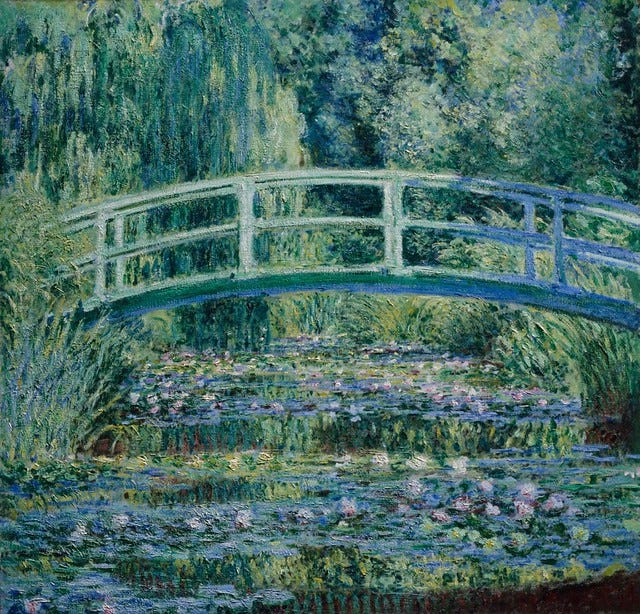

On the canvas, every detail stands out clearly. You can count the planks of the deck. The posts of the railings cut precisely against the immaculate white. The green of the wood shows bright against the snow. The reflections in the water are limpid, almost geometric.

Monet is 54. His eyes work perfectly. He sees contours, edges, tonal transitions. The bridge exists as an identifiable architectural structure.

The following summer, he also paints the bridge in sunshine. The same sharpness of forms.

The Peak

The vegetation has grown. In 1899, water lilies cover the water with their broad round leaves. Wisteria climbs along the banks.

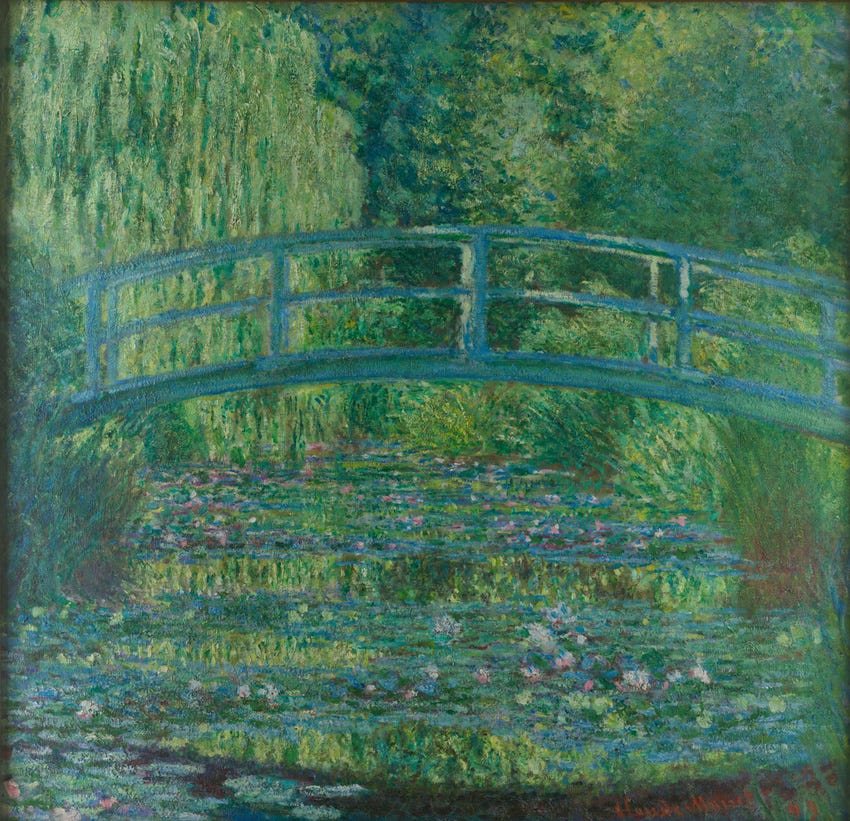

During the summer, Monet produces his most famous series of the bridge. At least twelve canvases. The green arch stands out against a tangle of trees and mauve flowers. Pink water lilies float on the water.

Monet applies his Impressionist touch in small juxtaposed commas. The bridge remains recognizable. Its curve, its posts, its structure are distinct. The water lilies form separate round patches, the leaves float individually.

He paints the same subject at different hours: misty morning, blazing midday, dusk. Ten easels lined up in the grass. A sketch for each moment of light.

This is his series method, already used for the Haystacks and Rouen Cathedral. In 1891, he had even paid peasants to delay felling poplars he was painting.

Monet is between 60 and 70. His sight is still good.

The Yellow Veil

In 1912, Monet squints at his easel. The green of the bridge escapes him, turns greyish. He rubs his eyelids. The blue of the water becomes murky, almost yellowish. The details of the railings blur, dissolve.

He is 72. For several months now, colours have been lying.

He consults an ophthalmologist.

Cataracts. Both eyes.

His doctor prescribes eucatropine drops. Monet writes to Dr Coutela: “It’s marvellous. I haven’t seen this well in a long time.”

The effect lasts a few months.

Then the cataracts worsen. Between 1912 and 1918, his vision deteriorates slowly. Blues turn grey, then disappear. Greens lose their brilliance. A yellowish filter settles over the world, thickening progressively.

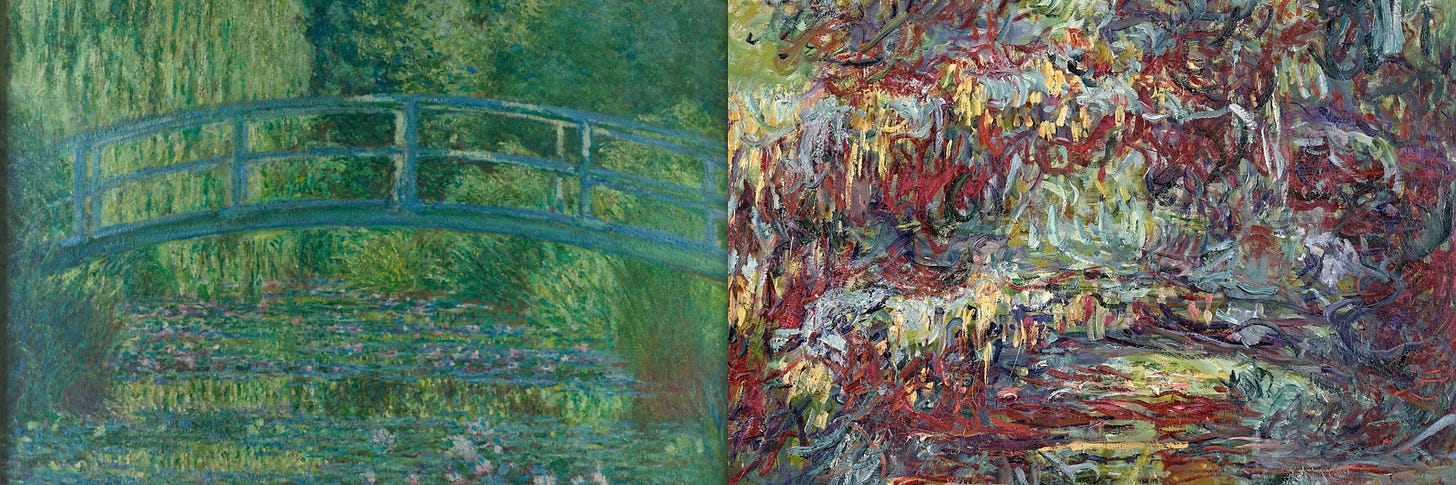

He continues painting the bridge. But on the canvases from this transitional period, change occurs. Contours become blurred. Colours drift towards warmer tones. The blue of the water shifts to greenish, then brownish. The pink of the water lilies turns orange.

The bridge begins to dissolve.