Frans Post: The First European Painter of the Americas

For 145 years, Europe only imagined the New World. In 1637, Frans Post went there. Discover the story of the first artist to document the Americas.

The cabin rocks. Frans Post opens his eyes in the darkness. The ship tilts, rights itself, tilts again. His stomach lurches. He clings to his narrow bunk, waits for it to pass. October 1636. Fourth week at sea.

Below him, in the lower deck where hundreds of soldiers and sailors are crammed together, it reeks of sweat and vomit. He hears groaning, curses in Dutch. Above his head, someone snores. Albert Eckhout, his cabin mate. A painter too, in his thirties, bearded, who smokes a pipe on deck when the weather permits.

Frans is 24 years old. He thinks of his brother Pieter who arranged all this. Pieter, the architect. The successful one. The one who works for the Nassaus, that princely family governing the United Provinces. Pieter recommended Frans for this expedition. Paint the conquered territories in Brazil. Document the Dutch possessions. A regular salary. A chance one doesn’t refuse.

Brazil. A colony wrested from the Portuguese six years earlier by the West India Company. The richest sugar region in the New World. The Company is now sending a new governor to administer it. Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen. 32 years old. Great-nephew of William the Silent, hero of Dutch independence. An ambitious man who wants to transform the colony. He’s brought an entire team. A naturalist to catalogue the fauna and flora. A physician to study medicinal plants. Two painters. Scientists. Nassau wants to make Brazil more than a trading post.

The days pass. Frans goes out when he can. Sketches clouds, rigging. Practises. In Haarlem, he learned to paint Dutch landscapes. Low horizons, grey skies, canals. But this New World, this land they call Brazil because of a red wood extracted from it, the pau-brasil, he doesn’t know. He imagines palm trees from sailors’ tales. Strange animals. The heat. But imagining is not seeing.

One January morning in 1637, the lookout shouts. Land. Frans climbs onto the deck with the others. On the horizon, a dark line. It has been 145 years since Christopher Columbus discovered America. No European painter has yet documented the landscapes of the New World.

The ship skirts endless beaches. Enters the mouth of three rivers that converge. Fortifications appear. Red roofs. Palm trees.

Recife.

Frans walks down the gangplank. The heat strikes him. A humid, thick heat. He sweats immediately. The air smells of green wood, sap, spices he doesn’t know. The sky is a violent blue. The light blinds him.

On the quay, African slaves unload crates. Dutch soldiers stand guard. Portuguese settlers watch in silence. The town spreads across a narrow peninsula. Low houses, dirt streets. In the distance, on a hill, blackened ruins. Olinda. Burnt by the Dutch in 1630 when they took the region.

Frans is assigned a house near the port. Two rooms. A packed earth floor. A window without glass. At night, he hears unknown sounds. Insects that chirp. Birds that cry out. Eckhout lodges in the neighbouring street. They meet in the morning, go together to the market to discover fruits they don’t know.

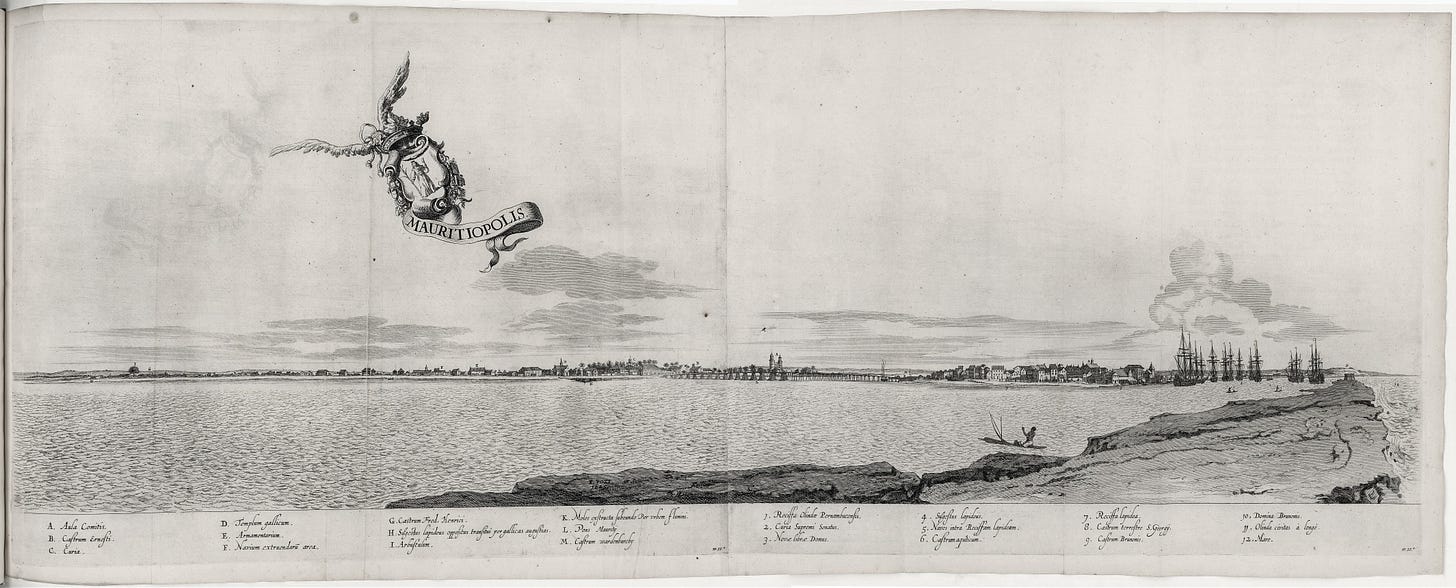

Nassau summons them a week after their arrival. The governor has settled on an islet facing Recife. Antonio Vaz Island. He receives Post and Eckhout in a room with bare walls. Sets out his vision. He wants to build a real city on this islet. Modern. With canals, bridges, straight streets like in Amsterdam. He’ll call it Mauritsstad.

Albert, you’ll document the populations. The natives, the Africans, the Portuguese. Their faces, their clothing, their customs. Frans, you’ll do the landscapes. The forts we’ve conquered. The sugar cane plantations. The villages. These canvases will decorate my palace.

Nassau gives each of them a horse, a guide, a pass signed by his own hand.