Leonora Carrington: The Woman They Coulndn't Destroy

She had everything an English aristocrat could want. Then Leonora Carrington chose love over luxury and art over safety. The price she paid will shock you.

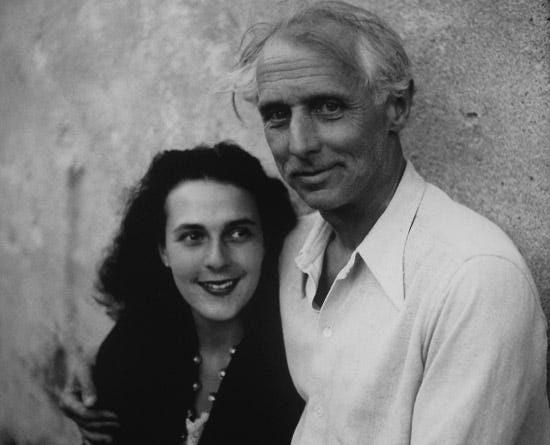

Saint-Martin-d'Ardèche, May 1940. Leonora Carrington sets two plates on the wooden table. She is twenty-three years old, a few brown strands escaping from her chignon. In the garden, Max Ernst carves a limestone sculpture. Forty-nine years old, greying beard, white shirt rolled up to his elbows.

Their meeting in Paris in 1937 had changed everything. Leonora was then attending Ozenfant's studio, having escaped the Lancashire aristocracy and her father Sir Harold Carrington. He owned textile mills, a considerable fortune and fixed ideas about his younger daughter's future: Catholic boarding schools, deportment lessons, a suitable marriage. But Leonora had been drawing fantastic creatures since childhood, nourished by Celtic tales told to her by her Irish nurse.

The 1937 Surrealist exhibition had sealed her destiny. Ernst had approached her canvases, had commented on the accuracy of her visions. Love at first sight had been immediate. Ernst left his wife, Leonora broke with her family. They settled first in Paris, then in this Ardèche of Southern France where they spent happy days.

A rumbling rises from the valley. Leonora freezes, a plate in each hand. Through the window, she glimpses a black Citroën struggling up the hairpin bends. Max continues his work, concentrated on the stone. The noise draws closer. Stops.

Car doors slam. Footsteps on gravel. Since the German offensive of 10 May, everything has collapsed. The Wehrmacht has bypassed the Maginot Line, swept over the Netherlands and Belgium. Max now represents an enemy to the French authorities: German national in occupied territory. Leonora knows what awaits him. She has already lived through this in September 1939 during Max's first arrest. Three days' internment as an enemy alien. André Breton and Paul Éluard had secured his release.

A knock. Three sharp raps. Leonora crosses the corridor. She opens.

Two gendarmes. The sergeant, grey moustache, képi pulled down. The younger one hanging back, hand on his revolver holster.

"Does one Ernst Max, of German nationality, reside at this address?"

She nods. The sergeant produces a crumpled warrant. Order from the Ardèche prefecture. Ernst Max will be transferred to Les Milles camp near Aix-en-Provence. Administrative internment. Duration indefinite.

Max appears in the doorway. His clear eyes settle on Leonora.

"Ten minutes?"

The sergeant checks his watch. Agrees. Max goes upstairs, stuffs belongings into a leather suitcase. Leonora follows him. He takes his manuscript of memoirs, a few drawings, a photograph of her. He places a finger on her lips.

"You know what you must do. The paintings are hidden in the cellar. If things turn bad, go to Catherine's in London."

Max kisses Leonora. His lips are dry. He gets into the Citroën, suitcase on his knees. The car drives away. The sound of the engine fades, is lost in the song of the cicadas.

Leonora remains standing. Around her, the hundred-year-old olive trees, the wild lavender, the vines they planted together. Three years of happiness ending in ten minutes.

She wanders from room to room, eyes reddened. Every object recalls his presence. She goes down to the village sobbing, crosses the square under embarrassed gazes.

In the bathroom, she opens the medicine cabinet. Takes out the bottle of orange blossom water for insomnia. Drinks a mouthful. The perfumed liquid slides down her throat. She waits. Nothing. Drinks again. The spasms arrive. She vomits in the basin.

The revelation strikes her. What emerges from her body is more than perfumed water. It is pain itself rising up and expelling itself. She begins again. Drinks. Vomits. Each spasm evacuates a little of this invisible filth that has been suffocating her since the arrest. War, injustice, separation. For twenty-four hours, this cleansing ritual. A few boiled potatoes. Red wine from their vineyard.

The days follow. The Belgian collapse, the Germans entering Paris on 14 June, Pétain's armistice. Leonora works in the vegetable garden ten hours a day. Digs, weeds, waters under the June sun. Her hands become covered with blisters. Her skin browns. Each drop of sweat evacuates the world's impurities. Through this frenzied labour, she convinces herself that she is purifying not only her body but the entire earth. A certainty grows within her: she is no longer a simple abandoned woman, but the instrument of a superior force.

In the village, attitudes change. Since Max's arrest, Leonora arouses mistrust and whispers. The shopkeepers serve others before her. Women cross themselves as she passes. This Englishwoman living alone disturbs. The mayor spreads rumours that she might be a spy.

One June evening, French soldiers in retreat accuse her of espionage. They have seen her collecting snails with a lantern near her house. To them, she is sending signals to German planes. They threaten to execute her. She listens without flinching. In her mind, bullets cannot reach her. Her purification work has made her untouchable, chosen to accomplish a mysterious task she does not yet understand.

Late June, the sound of an engine pulls her from her meditation. A dusty Fiat climbs the drive. Catherine emerges, an old English friend trained in psychoanalysis in Vienna. She is fleeing the Nazis like thousands of others. Attempting to reach neutral Spain. Catherine has made this detour through Ardèche to collect Leonora.

From the first hours, Catherine notices her friend's state. This detachment in the face of danger, this fixation on obscure symbols, these obsessive rituals. She recognises the signs of psychic collapse. In private, she warns Leonora. The unconscious might perhaps be seeking to eliminate a paternal figure. Max having replaced the rejected father.

Catherine insists on leaving for Spain. German troops are approaching the demarcation line. In a few days, the free zone might be occupied. Leonora finally agrees. She hopes to obtain visas in Madrid. To secure Max's release. Her plan: use family connections, play the Carrington name.

Early July, they take the road in the Fiat. Leonora brings a suitcase marked with an engraved plaque: RÉVÉLATION. Near Andorra, the car breaks down. The brakes jam for no reason. Catherine curses. Leonora sees it as a cosmic sign. Like this faulty mechanism, something within her refuses to advance, paralysing her from the inside.

The journey resumes towards the Spanish border. Dusty roads, military checkpoints, refugees by the thousands. Catherine drives day and night to reach Madrid before the situation worsens. In the overheated passenger compartment, Leonora begins confusing the silhouettes of soldiers with those of businessmen in suits she has always hated. These uniforms, these scrutinising gazes, this authority that breaks lives remind her of everything she fled when leaving her father.

Madrid, late July 1940. The Francoist capital bears the stigmata of the civil war ended a year earlier. Facades riddled with bullet holes, gutted buildings, leaden atmosphere. Leonora does not speak Spanish, which reinforces her disorientation. Her body betrays her: she staggers while walking, loses balance, clings to walls like a wounded crab. Her legs refuse to walk straight.

From the first day, she observes the men in black who patrol the avenues. Civil servants, policemen, dignitaries of the regime. They all wear the same glacial authority, the same brutal assurance. In her wavering mind, these silhouettes merge into a single figure: the incarnation of all fathers, all masters she has always fought. She christens them "Van Ghent" after a painting from her childhood that terrified her. To her, these men have hypnotised all of Madrid, transformed the population into submissive puppets, exactly as her father had tried to transform her into an obedient wife.

Her behaviour becomes erratic. One evening, convinced that newspapers spread Van Ghent's hypnotic orders, she rushes at a newspaper kiosk. Tears off armfuls of daily papers. Methodically rips each page, throws the black fragments to the wind like confetti. Passers-by stop, aghast, before this woman screaming incomprehensible words in English. Her hands bleed, lacerated by newsprint. She feels nothing.

A Falange officer spots her. Forcibly brings her back to the hotel. At dawn, in the luxurious lobby, Leonora sees the incarnation of her nightmare emerge: Van Ghent accompanied by a silhouette she takes for his son. Real or hallucinated figures, they accuse her of madness and obscenity. Terrified, she flees to a neighbouring public garden. Begins playing in the grass like a child, under the amazed eyes of passers-by.

Catherine can no longer manage the situation. Her friend is sinking into psychosis. In a moment of lucidity, Leonora begins to grow suspicious. She notices that Van Ghent offers her cigarettes unavailable in wartime. Suspicious detail. She elaborates her theory: Hitler and his accomplices conduct war through collective hypnotism. In Spain, the network would be directed by Van Ghent, paternal incarnation. To stop the world conflict, one need only pierce this secret.

She presents herself at the British embassy. Exposes her theory to the appalled consul. By uniting Spain and England, one could free the world from collective hypnosis. The consul contacts Dr Martinez Alonso. This man with the severe face, authoritarian manners, embodies for Leonora everything she has fled since adolescence. Immediate diagnosis: acute dementia. Another man who wants to control her, reduce her to silence, bend her to his will.