The Caravaggio Code: The Secret Nobody Saw for 400 Years

It took four centuries to spot it. Hidden in a basket of fruit, a secret symbol used by early Christians to avoid execution. The true story of the hidden message in The Supper at Emmaus.

Spring, year 30. Two men leave Jerusalem and take the road to Emmaus. Three days earlier, their master died crucified. This morning, women found his tomb empty. They speak of angels, of resurrection. The two discuss, doubt, try to understand.

A stranger joins them and listens to their story. He begins speaking of sacred texts, of prophets, of what has been written since the beginning. His voice sounds strangely familiar, though they cannot tell why.

Evening falls. Arrived at their destination, they enter an inn. The man makes to continue his journey; they insist he stay. Everyone sits down to supper; the innkeeper brings bread, wine, roasted chicken, a basket of fruit. The stranger takes the bread, raises his hand, pronounces a blessing and breaks the loaf.

At that precise instant, the two disciples understand. It is him. Jesus, whom they saw die three days earlier. Their eyes open suddenly. One rises abruptly, grips the armrests of his chair. The other spreads his arms in a cross, mouth agape, palms towards the sky. Jesus watches them calmly. He vanishes before their eyes.

This scene, Caravaggio paints in 1601. He is 30 years old and all Rome speaks of him.

He has just completed three paintings for the church of Saint Louis of the French that caused a sensation: a murder, a conversion, a saint writing. His style strikes the imagination. He illuminates his figures as though on a theatre stage and plunges everything else into absolute darkness. His saints have dirty feet, his apostles resemble labourers from the docks.

The Roman aristocrat Ciriaco Mattei commissions from him The Supper at Emmaus for his private collection. Caravaggio chooses to freeze the exact instant of recognition, the moment when the miracle becomes visible.

At the centre of the painting, Jesus blesses the bread. He is 33 years old but his face is strangely young, beardless, almost feminine. This is no error: in the biblical texts, it is written that Jesus reappeared “in another form” after his death. Caravaggio takes the text at face value and paints an unrecognisable Christ.

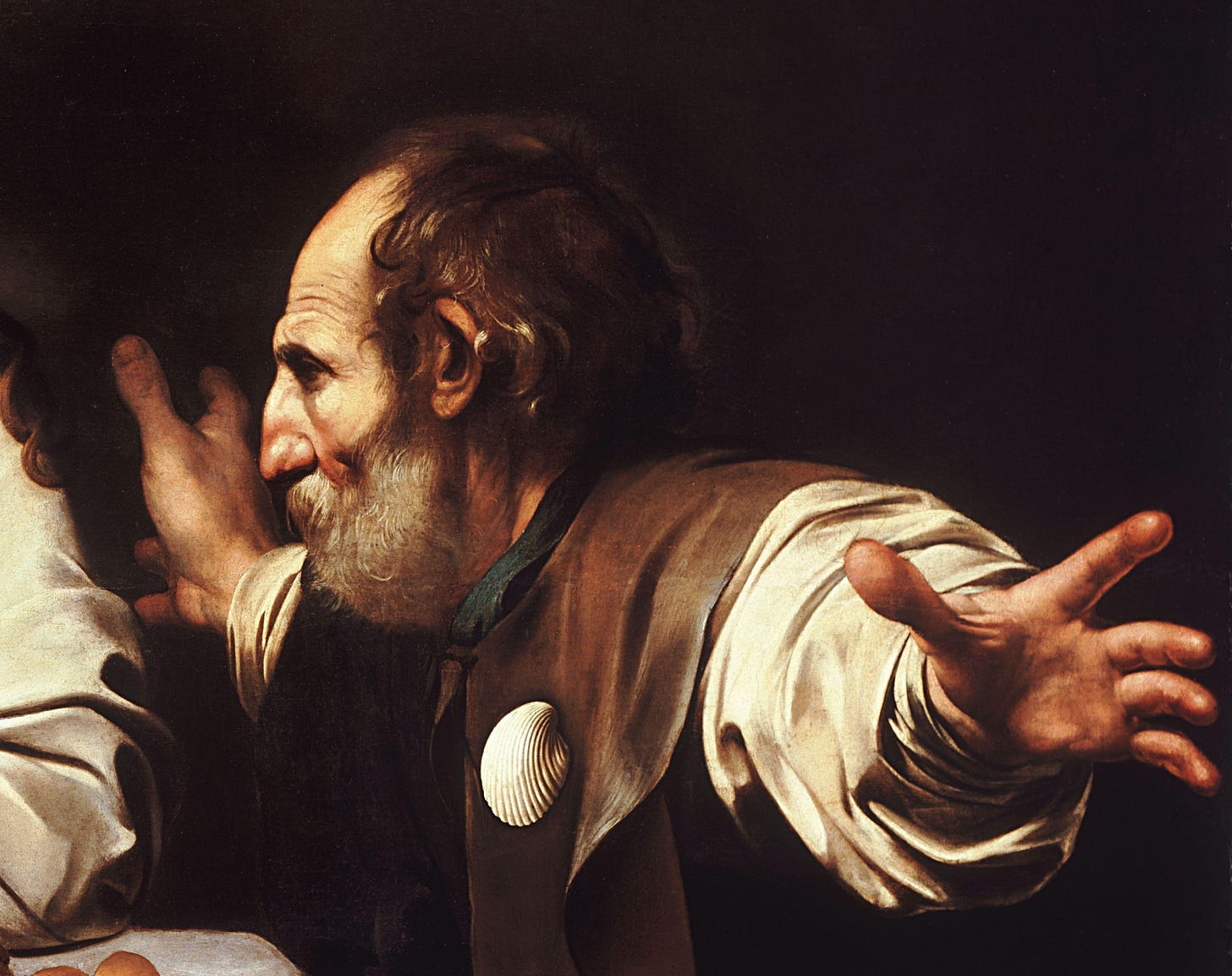

To the right of Jesus, Cleophas straightens abruptly, hands clenched on the armrests of his chair. On his cloak, a shell: the symbol of pilgrims who walk towards holy places, the emblem of those who seek God.

On the left, the other disciple spreads his arms in a cross, palms open, as though to verify he is not dreaming. Behind Jesus, the innkeeper observes without understanding. His face remains in shadow whilst those of the disciples bathe in light. He sees three men dining, nothing more. Caravaggio opposes two types of vision: that which perceives the divine and that which remains blind to the miracle.

On the table, the objects all carry a double meaning. The bread and wine refer directly to the Catholic Mass: the priest blesses the bread which, according to doctrine, becomes the body of Christ. Here, Jesus repeats the same gesture as at his last meal before dying.

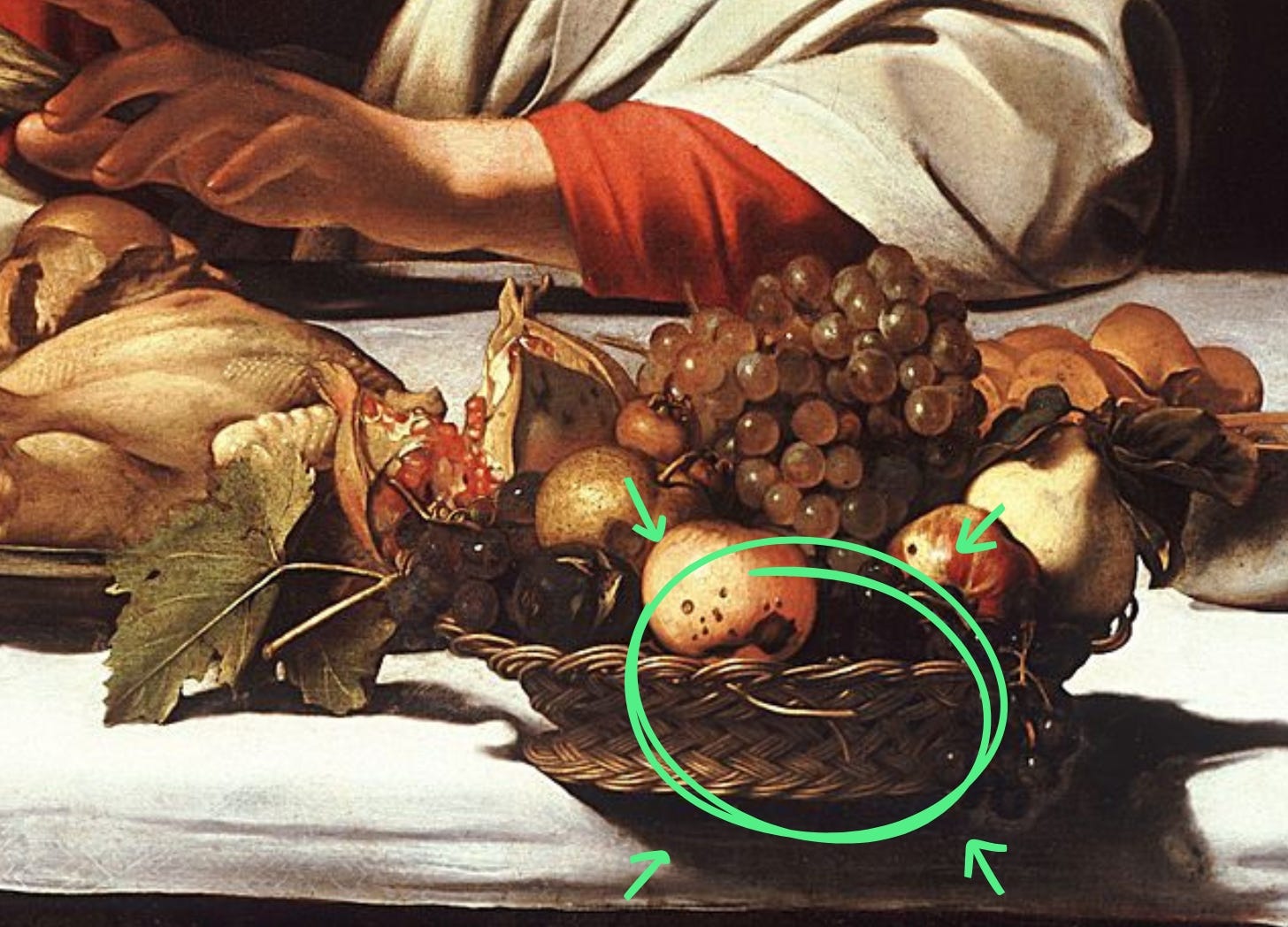

The grapes in the basket evoke wine, thus blood. In Christian iconography, the grape pressed to obtain wine symbolises the sacrifice of Christ whose blood flowed on the cross.

The split pomegranate recounts the resurrection: this fruit, when it bursts, releases hundreds of red seeds. From apparent death (the envelope that breaks) emerges a multitude of new lives. It is the very image of victory over death.

The apples recall original sin, the fault committed by Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, which the coming of Christ erases.

The basket overflows, placed in balance at the edge of the table. It appears about to fall towards us. For centuries, specialists have admired this still life. The hanging leaves, the fruit painted with impressive realism, the wickerwork woven meticulously. Too perfect, perhaps.

In 2019, Kelly Grovier, cultural critic at the BBC, examines the painting very closely for an article. He spends hours scrutinising the basket, observes the weave of the wicker. Two strands have come loose from the plaiting. One extends upwards, the other downwards. They cross in the middle.

Grovier freezes. This shape, he knows it. A stylised fish. The symbol of the first Christians: the ichthys.