The Last Day of Vincent Van Gogh

One day. One painter. One decision. Last painting. Discover hour by hour Vincent Van Gogh's final day.

Auvers-sur-Oise, Sunday 27th July 1890

Five o’clock strikes from the bell tower of Notre-Dame. Vincent van Gogh opens his eyes in his attic room. Seven square metres beneath the roof of the auberge Ravoux. A narrow bed, a washstand, a cupboard. The skylight admits the first glimmers of dawn.

He rises with practised ease. At thirty-seven, his face bears the marks of past crises. Outside, cockerels crow in the village backyards. Vincent passes his hands over his gaunt face, smooths his ginger beard. He dresses slowly. Canvas trousers, white shirt, jacket worn at the elbows. The same ritual for two months since he took lodgings here at three francs fifty a day.

He descends the narrow staircase. In the corridor, he passes Adeline Ravoux coming up, arms laden with laundry. The thirteen-year-old girl smiles. “Good morning, Monsieur Vincent.” “Good morning, Adeline.”

His voice carries a slight Dutch accent. Adeline continues her ascent. Since May, she has observed this discreet lodger who speaks hesitant but comprehensible French. Always polite, never raising his voice. He paints every day, a man of routine whose regularity proves reassuring. Everyone knows he has returned from the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, but in Auvers, nothing in his behaviour causes alarm.

Vincent pushes open the door to the common room. Arthur Ravoux arranges chairs around the oak tables. The forty-one-year-old innkeeper, a former butcher turned manager since 1889, greets his tenant with a nod. A respectful relationship between two men who understand each other without many words. “Coffee, Monsieur Vincent?” “Gladly.”

Through the window panes, Vincent glimpses the Place de la Mairie awakening. A cat crosses the street. Shutters open one by one. Auvers emerges from the night. He settles at his usual table.

The staircase creaks. Anton Hirschig descends in turn. This twenty-three-year-old Dutch painter has been sharing the lodgings for several weeks. He greets Vincent in Dutch. Vincent looks up, responds in their common tongue. Their exchanges often remain limited to these morning pleasantries. Hirschig takes another table.

Madame Ravoux brings breakfast. Bread, butter, jam. Vincent eats without appetite. His thoughts drift towards that stormy conversation he had with Theo during his visit to Paris on 6th July last. His younger brother, aged thirty-three, employed at the Boussod Valadon gallery on boulevard Montmartre, has been supporting him financially for years. One hundred and fifty francs a month sent religiously. A generosity that allows Vincent to dedicate himself to his art.

But Theo’s burdens have grown heavier since his marriage to Johanna Bonger in April 1889. A son was born in January, little Vincent Willem whom Vincent cherishes. These new family responsibilities worry the painter. During that last Parisian visit, he discovered his brother’s mounting financial difficulties. This reality distresses him. He feels himself a burden to this brother who has already given so much.

Vincent finishes his meal quickly. In his room, he gathers brushes with worn bristles, nearly empty tubes of paint, his stained palette. These colours he often buys from old Tanguy, that good merchant on rue Clauzel who extends credit to artists. Julien Tanguy, sixty-five years old, believes in his talent when all Paris ignores it.

Vincent loads his portable easel, descends again with his paint box. Arthur Ravoux and Adeline exchange a surprised look. In the two months he has lodged here, Vincent never leaves before nine o’clock.

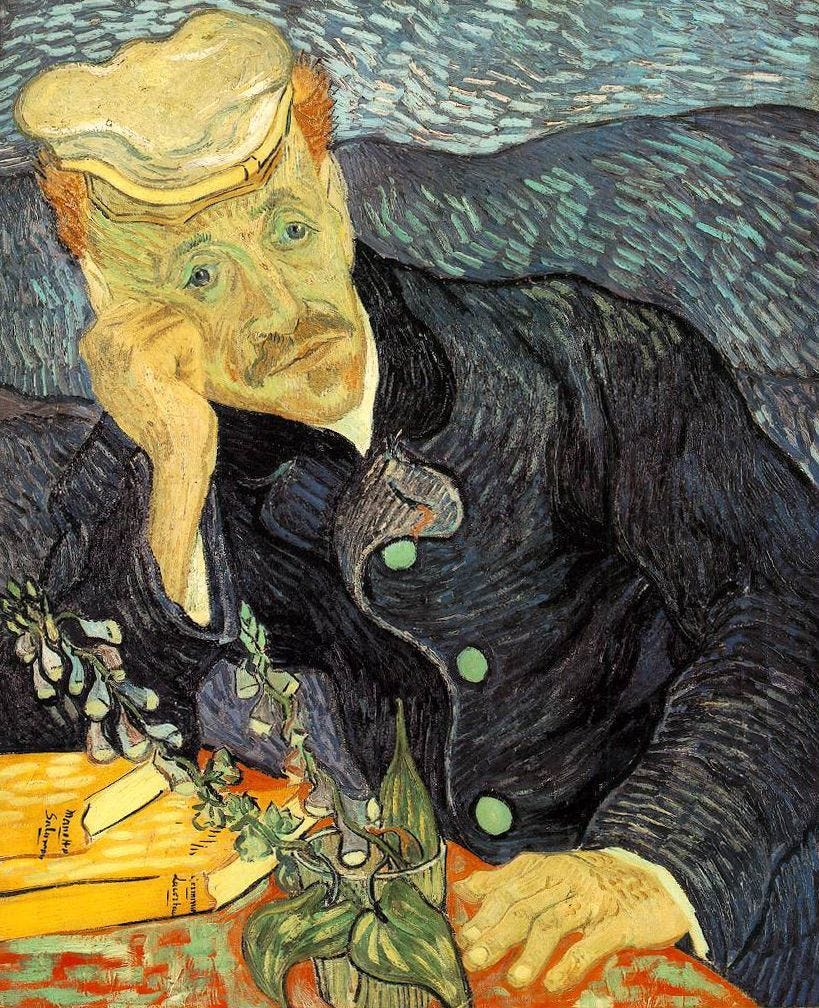

Vincent takes the rue Daubigny. This path he knows well. It is the one he regularly takes to visit Doctor Paul Gachet. This sixty-two-year-old physician, a specialist in melancholy, was meant to watch over his fragile mental health. Recommended by the painter Pissarro, Gachet knows about nervous disorders. In reality, their relationship is primarily friendly. Gachet appreciates art, paints in his spare time, possesses a fine collection. Vincent painted his portrait in June, a pensive face resting on the hand, melancholic gaze.

Vincent sets himself up facing the embankment where tangled tree roots grow. He mounts his easel, takes out his canvas. This complex motif has attracted him since yesterday. These tortuous roots, laid bare by erosion, form a chaotic network. He begins to paint, applying the colour directly from the tube.

Minutes pass. Vincent traces, erases, begins again. The forms do not obey him. His hand hesitates. He senses that nothing will ever change. All these canvases painted in general indifference, this work that nobody understands. What is the point of continuing? He had nevertheless maintained hope for recognition, however modest, for so long. Just a few benevolent glances cast upon his work.

He recalls that phrase he had written to his brother: “One day or another, I believe I shall find a way to mount an exhibition of my own in a café.” A humble ambition. He asked no more than that. But even this seems impossible. In Arles, children pursued him shouting, pointing fingers at him. His canvases disturb, unsettle. Only Theo and a few rare friends like Gachet or Tanguy understand his painting. The world remains closed to him.

At the inn, midday strikes. Arthur Ravoux consults the clock. Monsieur Vincent, always punctual for meals since his arrival at the end of May, is conspicuously absent. “Has Monsieur Vincent told you anything today?” he asks Adeline. “No, Papa. Everything seemed normal this morning, apart from his leaving earlier.”

Adeline steps out into the street, looks into the distance. No figure in sight. The July sun beats down. Vincent has perhaps sought shade elsewhere.

Vincent continues his painting. The forms elude him. He sets down his brush, studies his canvas. Dissatisfaction overtakes him. The impression of going in circles, of no longer advancing.

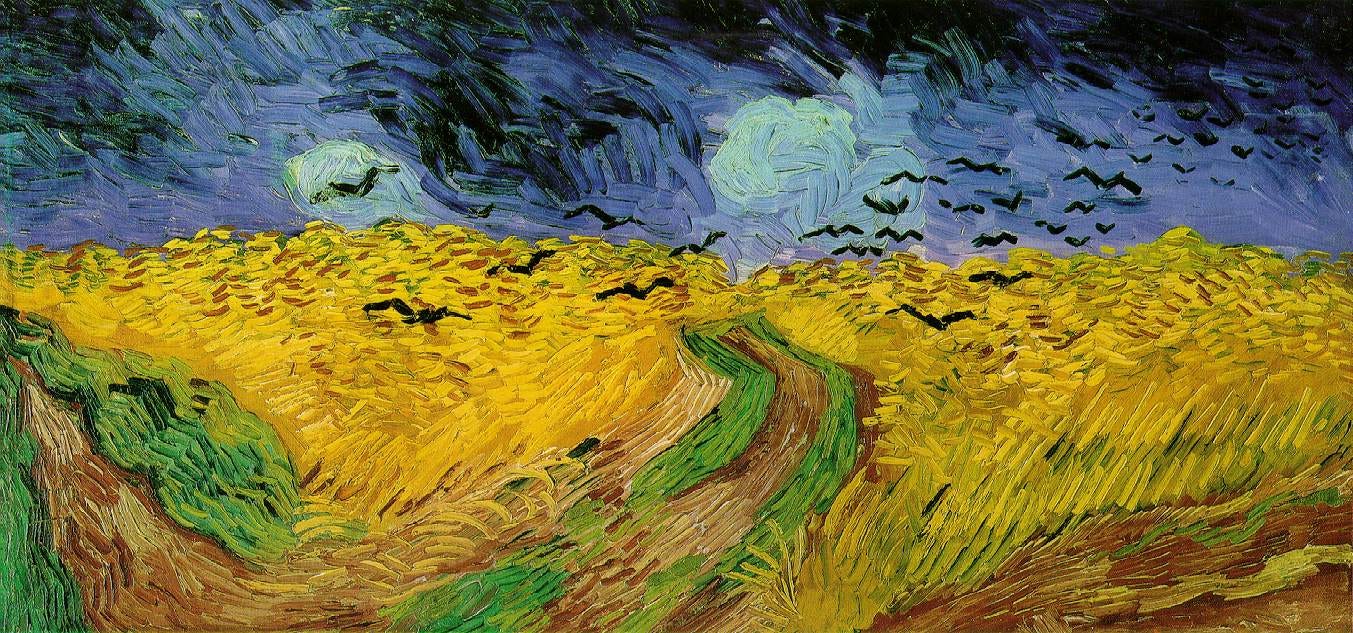

Towards five o’clock, Vincent packs away his equipment abruptly. His canvas remains unfinished. He heads towards the heights of the village with purposeful stride. The path climbs behind the dilapidated château that dominates Auvers. Up there stretch the wheat fields belonging to Monsieur Gosselin, an absent Parisian landowner.

Vincent climbs the slope beneath the burning sun. More than half a kilometre’s walk through rural paths. The ripe wheat ripples in the wind, dotted with poppies. He crosses through the golden ears, plunges into the heart of this vegetal sea that isolates him from the world.

Eighteen twenty. Vincent stops in the middle of the field. He takes a revolver from his pocket, a weapon he has owned only recently. The metal gleams in the sunlight. His hand trembles. A second’s hesitation. Then Vincent points the weapon towards his chest and fires.