The Painting That Obsessed Hitler Freud & Lenin

Freud kept it by his couch. Lenin above his bed. Hitler paid a fortune for it. By 1900, it hung in nearly every Berlin home. Discover the story of The Isle of the Dead.

Florence, spring 1880. A widow from high society visits the studio of a Swiss painter. She stops before a canvas in progress. A rocky islet. A dark sea. Cypresses standing like black flames.

Marie Berna wants this painting. But with an addition.

Arnold Böcklin is 53 years old. Behind him, eight children dead out of fourteen. His young daughter Maria rests in the city’s English cemetery. These bereavements nourish his imagination. The client commissions a personal version. She requests a funerary element. Böcklin incorporates a figure draped in white into the boat approaching the island. At its feet, a white coffin.

The landscape shifts. The craft becomes a crossing towards the beyond. The boatman evokes Charon. The rocky isle resembles the final resting place. Böcklin even returns to his first version to add the veiled woman and the coffin. He decides to produce several copies of this dream image.

Between 1880 and 1886, five versions are born. All slightly different. The first two bathe in the orange glow of a setting sun. The third, painted in 1883, presents a paler sky, almost diurnal. In the fourth and fifth versions, the cliffs become lighter and taller, as though sculpted by human hand. The horizon brightens. Böcklin gradually abandons the nocturnal atmosphere for a more architectural evocation, without ever dispelling Death’s shadow.

The painter will give no title to these canvases. It is his Berlin dealer, Fritz Gurlitt, who finds in 1883 the name “Die Toteninsel”. The Isle of the Dead. Böcklin remains sparing with explanations. He contents himself with writing that he wished to paint “a dream image which must be so tranquil that the slightest knock at the door would make you start”.

The success, initially discreet, becomes lightning swift. Fin-de-siècle Europe enthuses over this evocation of the soul’s final journey. Gurlitt, visionary, organises vast reproduction campaigns. In 1885, the artist Max Klinger creates a print issued in multiple copies. Then come thousands of photomechanical reproductions for the Germanic market. The image enters homes. Into the collective imagination.

At the turn of the 20th century, one finds a reproduction of The Isle of the Dead in almost every Berlin household. Vladimir Nabokov would later write of witnessing this vogue. The painting becomes a popular icon. Its image is so widespread that it appears familiar, whilst retaining its power to disturb.

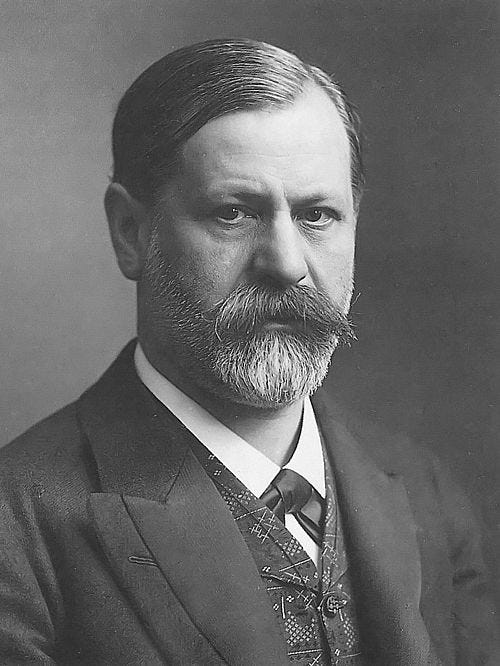

In this context, three men will develop an obsession with this canvas. Three radically opposed trajectories. Sigmund Freud, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Adolf Hitler. Each will hang an image of The Isle of the Dead in his home.

Freud and the dream of the isle

Vienna, late 1890s. Freud is 40 years old, developing a method for analysing the mind. Böcklin’s canvas haunts his imagination to the point of appearing in his dreams. In The Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1899, he recounts one of his own dreams. He sees himself standing on a cliff in the middle of the sea, in Böcklin’s style. A man stands on the rock of the mysterious island.

Analysing this dream, Freud associates the glimpsed figure with Captain Dreyfus, that French Jewish officer unjustly imprisoned on Devil’s Island in a scandal then shaking Europe. His unconscious has blended current events with Böcklin’s imagery to express his anxieties about mounting antisemitism.

The canvas hangs in his consulting room on Berggasse. Among the antique statues and Ingres’s Oedipus Confronting the Sphinx, the engraving of The Isle of the Dead stands near the couch where his patients recline. Freud never expressed himself publicly on this choice. He who examines the depths of the human soul found in this frozen dream image a symbol of what he would later theorise as Thanatos. The death drive that coexists with the life force.

In 1938, Freud flees the Nazi regime, goes into exile in London. He takes his antiquities and precious objects, recreates his consulting room identically. Until his death in 1939, aged 83, he will keep this funereal landscape beside him.

Lenin and his exile room

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin is 14 years younger than Freud. Fervent Marxist, strict materialist, hostile to the spiritualisms of old bourgeois culture. Yet he too will fall under the spell of Böcklin’s landscape.