The True Story Behind Hokusai’s Great Wave

Did you know The Great Wave wasn't the first? From the failed sketches of 1797 to the 1831 masterpiece, discover the story of Hokusai’s lifelong battle.

Spring 1797, Edo. Katsushika Hokusai steps back three paces, studies the sketch before him. The wave refuses to come alive. He moves closer, crumples the paper, tosses it across the studio. The basket at the back already overflows. Three weeks now that he has been starting over.

His studio in the Katsushika district accumulates failed sketches, stacked cardboard, filth. His first wife died four years ago, leaving him with three children. He remarried last year. He hates cleaning. When the studio becomes unbearable, he simply moves elsewhere. He also changes his name every five years or so, like many Japanese artists, but he takes the practice further than anyone.

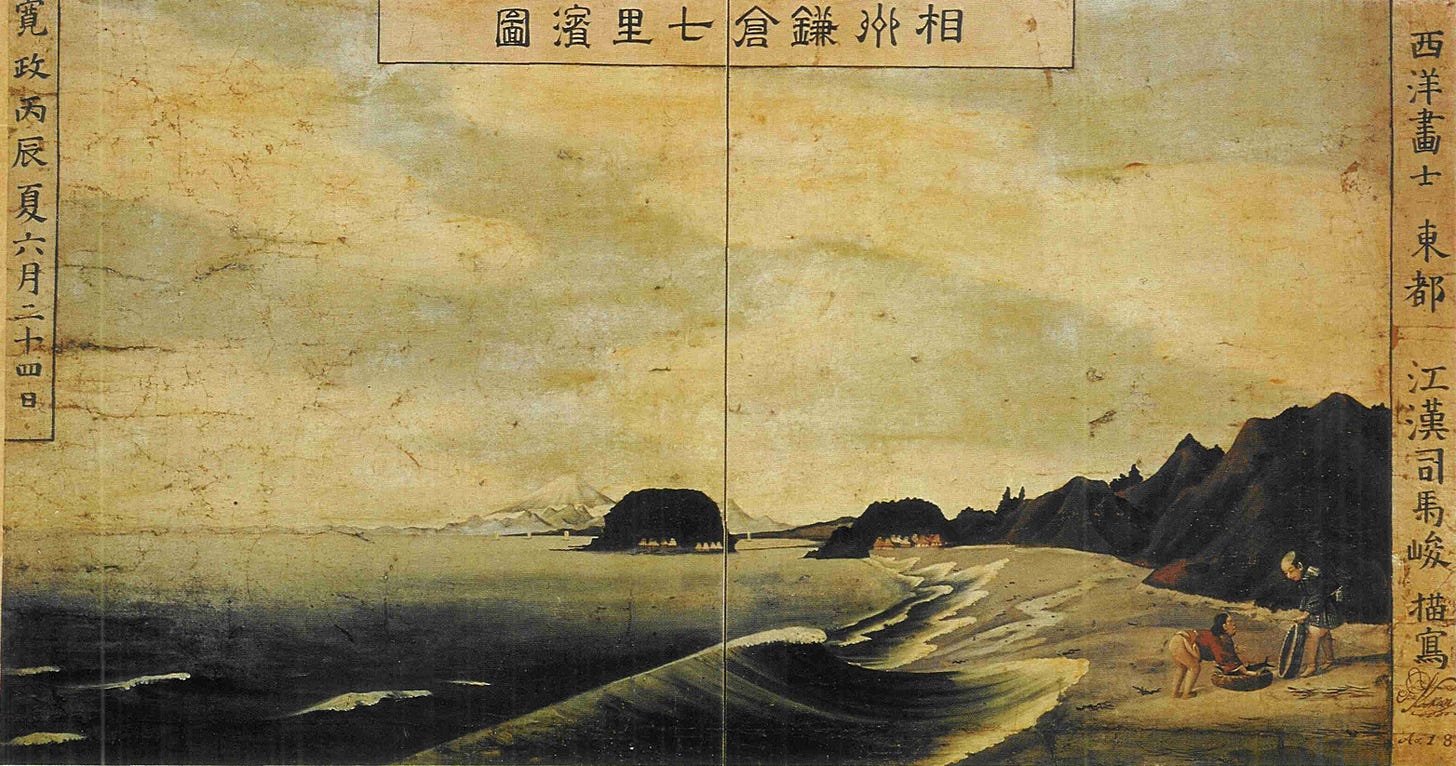

Last year, in a city gallery, he stopped before a painting by Shiba Kōkan. Kōkan is a Japanese artist who frequents the Dutch, those foreigners permitted to dock at Nagasaki since the country closed in 1639. He has brought back their techniques, their way of structuring space, of creating depth. The painting fascinated him. He cannot stop thinking about it.

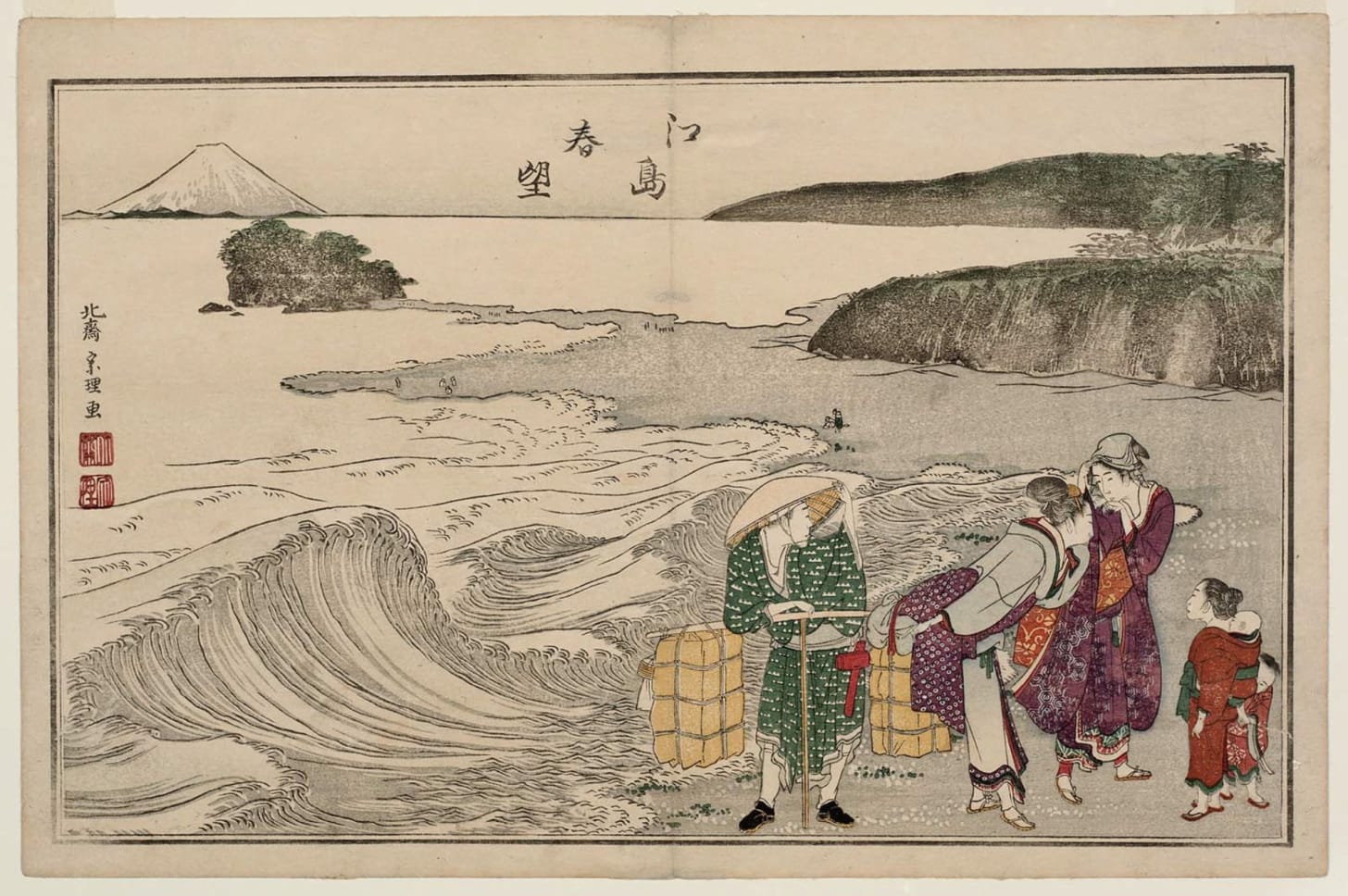

He takes out a fresh sheet, begins again. Strollers gaze at the sea from the beach of Enoshima, Mount Fuji appears tiny on the horizon. The wave spreads across the shore, trapped on the left side. But the sea sleeps.

1803

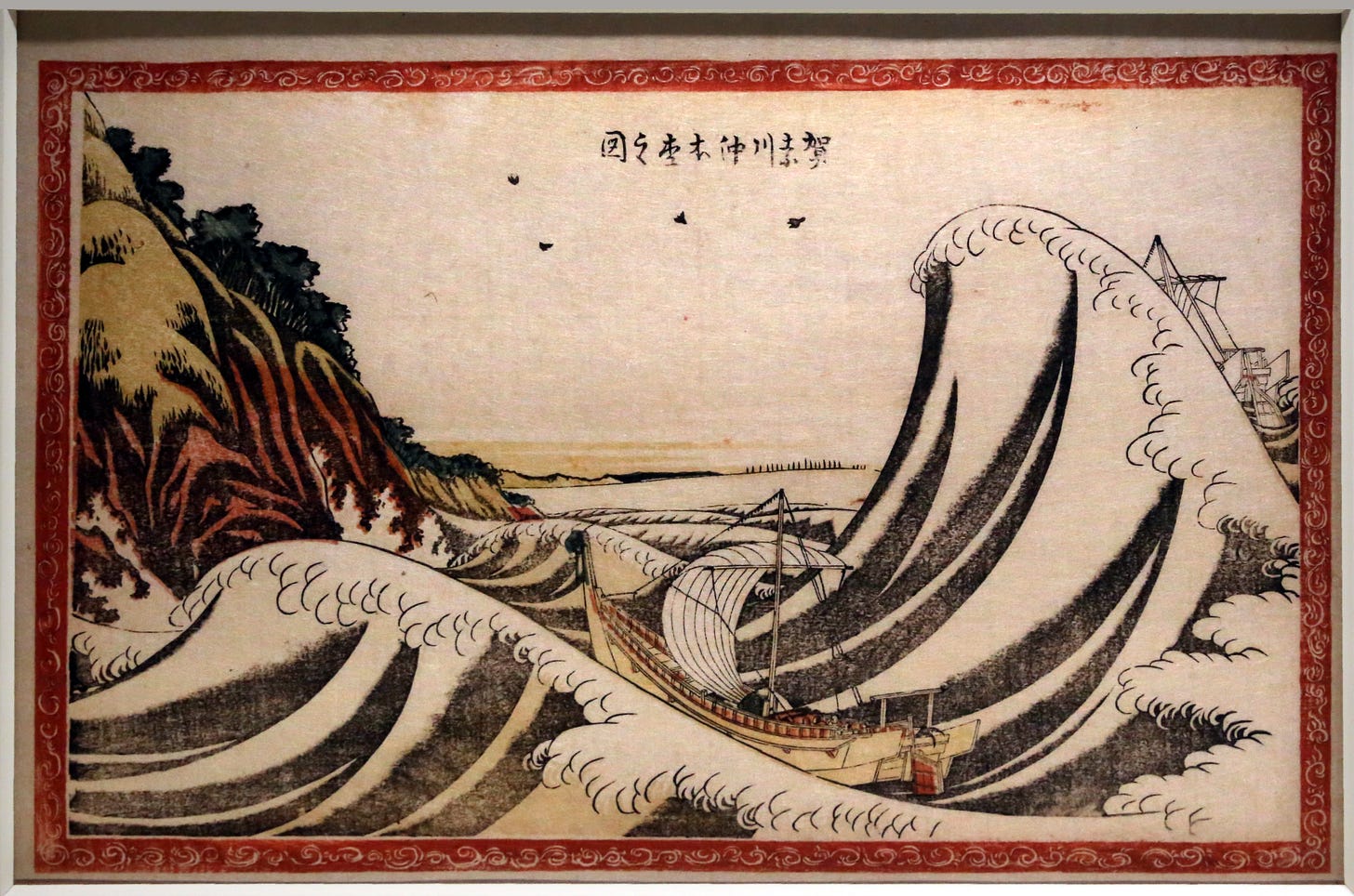

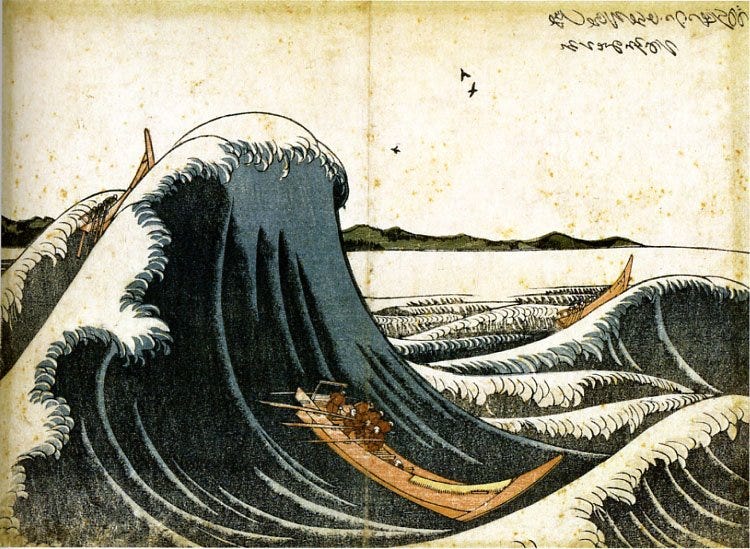

Six years have passed. Hokusai has changed his name twice, moved at least ten times. At 44, he engraves View of Honmoku off Kanagawa in a new studio in the printmakers’ district. This time he removes almost everything: the strollers, Mount Fuji. The wave invades the image, occupies two thirds of the space. A vessel cuts through the water nearby, shrunk to heighten the contrast.

But the blues remain pale, the vegetable indigo fades in the sun within months. On the finished print, the wave is there but does not move, stylised crest, almost mineral. He files it with the other attempts.

The Turning Point

In 1804, Hokusai is 44 and lives off modest commissions. During a Tokyo festival, he sets up buckets of ink and a broom in the middle of the street. He paints a portrait of the Buddhist priest Daruma 180 metres long on the ground. People stop, watch, talk. The story reaches the ears of the court.

A few months later, a summons. The shogun, the military leader who governs Japan, invites him to the palace for a competition. His opponent is Buncho, a master recognised for decades. Hokusai has never set foot in these places.

When the day comes, Buncho paints a landscape of perfect mastery. Hokusai observes, waits his turn. He traces a broad blue curve on the paper, takes a chicken from a cage, dips its feet in red paint, releases it onto the canvas. The animal runs across the paper, leaving traces that form maple leaves floating on the Tatsuta river. The shogun laughs. Hokusai wins the competition.

He returns home with a new reputation. For the first time in years, he has money, assured commissions. He can choose his subjects. That same year, he returns to his obsession, engraves Fast Cargo Boat Confronting the Waves. Seven years since he last touched this image.

He makes a decision: move the wave from the left side to the right side. It now breaks from the right, engulfs the boat from the left. This configuration will not change again.